Considered to be perhaps the most commonly experienced movement disorder associated with sleep disorders, many who have RLS have easily passed it up for plain restlessness, while others barely notice their unusual movements and anomalous sleep behavior save for observations made by their bed partner. According to the set classification of sleeping disorders laid down by the ICSD-2 – International Classification of Sleep Disorders – 2nd Edition, Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) is pegged under Sleep-Related Movement Disorders, together with other conditions in the same class such as PLMS (Periodic Limb Movement in Sleep) and Bruxism, among others.

( RLS – Image Courtesy of www.uratex.com.ph )

Gray Area In Diagnosing Restless Leg Syndrome

Unlike most of the other sleeping disorders which have elaborate diagnostic measures established for their testing and analysis, the same is not so for RLS. Therefore Restless Leg Syndrome is identified purely from observation of clinical features and symptomatic manifestations as there no lab tests for RLS or diagnostic testing metrics available. Guiding this is the standard of various criteria as stipulated and established in the year 1995 (and later revised moderately in the year 2003) by (IRLSSG) which is the International Restless Leg Syndrome Study Group.

( IRLSSG logo – Image Courtesy of irlssg.org )

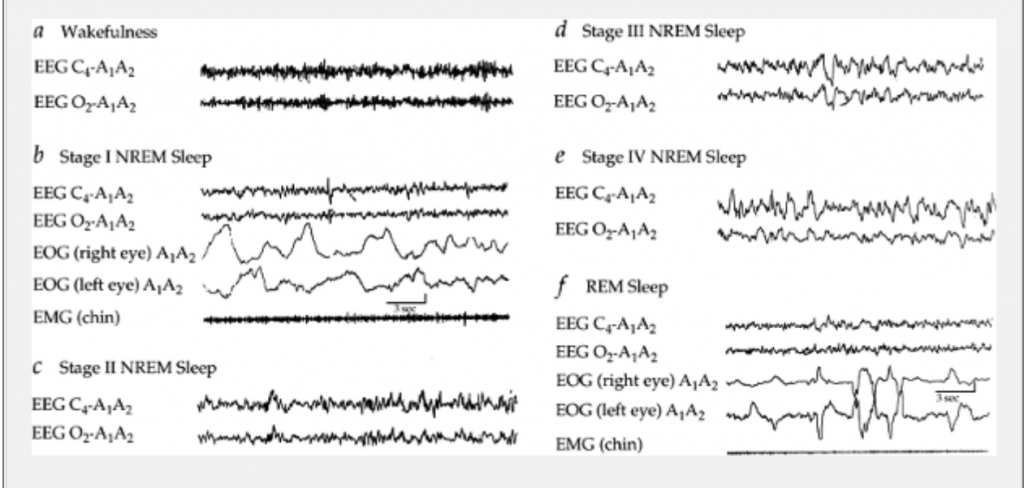

Before the standardization of the diagnostic criteria for RLS back in the middle of the 20th century, the description of the condition was vaguely defined let alone diagnosed. Since then, it is now no longer a gray area with regards to definition and diagnosis, and is clearly identified using 4 primary criteria for diagnosis. These criteria are based on two broad categories, behavioral and physiological benchmarks, which further classify the sleep phase into two stages: NREM (Non Rapid Eye Movement) Sleep and REM Sleep (Rapid Eye Movement). The NREM stage has 3 stages – N1 stage, N2 stage, and the N3 stage. Therefore the entire sleep phase is assessed based on the progression of behavioral and physiological changes manifested in the sleeper from the N1, N2, N3 stages of NREM sleep and on to REM sleep.

( Sleep Stages by EEG-EOG-EMG – Image Courtesy of universitipetronas.hostoi.com )

RLS is more appropriately defined as a neurological disorder (as opposed to a sleeping disorder) which affects both sensory functionality and motor functionality in the affected person. It typically affects the person all their life and may be detected from their earlier years when young but often are the cases diagnosed later on in the middle ages or even in old age.

( RLS – Image Courtesy of www.health.com )

Susceptibility of RLS

The prevalence of RLS cases has been shown to grow with increasing age; further, though the reason for which is unexplained, it reaches a plateau phase between the 85 and 90 age bracket. There is also a higher likelihood for women more than men to have RLS which is indicated to both progressive and chronic.

Further scientific research has revealed that it has some strong genetic links, particularly affecting family relations of the first degree, of whom RLS incidence was found to be about 40% to 50% for cases where the relative is suffering from primary or idiopathic Restless Leg Syndrome. Prevalence was shown to be even higher, at 83%, in identical twins (of the same zygote or monozygotic siblings).

( Monozygotic Identical Twins – Image Courtesy of www.dailymail.co.uk )

( Monozygotic Identical Twins – Image Courtesy of genetics.thetech.org )

In addition to these findings, it also came to light, following sophisticated analysis in segregation, that there are a number of specific genes associated with or resulting in the occurrence of Restless Leg Syndrome in given cases with dominant inheritance of autosomes. The analysis in linking and segregation set aside 5 distinct chromosomes, 14Q, 12Q, 22P, 2P, and 9P, associated with inherited RLS.

( Monozygotic Identical Twins – Image Courtesy of abcnews.go.com )

Clinical Manifestations and Symptoms of Restless Leg Syndrome

Sensory functionality is affected symptomatically by RLS in any or all of the following ways:

Intensely Discomfiting Feelings, Cramps, Tingles, Aches, Itches, Creepy sensations, Burning sensations, Razor-like sensations.

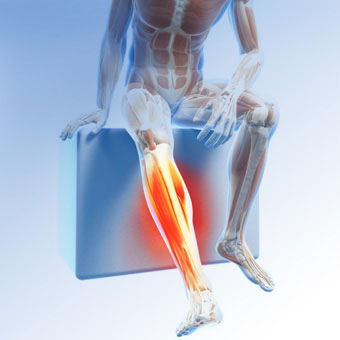

( Restless Leg Syndrome – Limb Section – Image Courtesy of www.medicinenet.com )

Notably, the affected person will experience the above sensory symptoms in their limbs, particularly in the region that runs down from the knees to the ankles. Typical complaints presented are that patients experience strong urges to move their legs about so as to achieve some relief from these sensations. Other parts of the body may experience the RLS sensational symptoms, including the arms, and this is mainly attributed to the more progressed phases of the condition.

( RLS – Image Courtesy of www.health.com )

Another factor that could lead to advanced manifestation of sensory symptoms to other parts of the body is when the affected person also has a Hypermotor Syndrome (RLS augmentation). In this case, the augmentation may take place up to about 2 hours in advance, occurring with greater intensity that spreads on to the rest of the body. This usually pertains to cases where the affected has been on long-term treatment with Dopamine-inducing psychoactive prescriptions (such as anti-psychotics, some antidepressants, and mood stabilizers).

( Dopamine Drugs and RLS – Image Courtesy of www.rlcure.com )

Timing of the manifested body movements usually occurs in the later hours (evening to nighttime) while the affected person is lying in bed. There are however, certain severe RLS cases where the patients have complained of experiencing the body movements even during the day, while awake but rested or seated.

( Prevalence: Idiopathic RLS and Secondary RLS – Image Courtesy of www.medscape.com)

Co-morbidities Linked to Restless Leg Syndrome

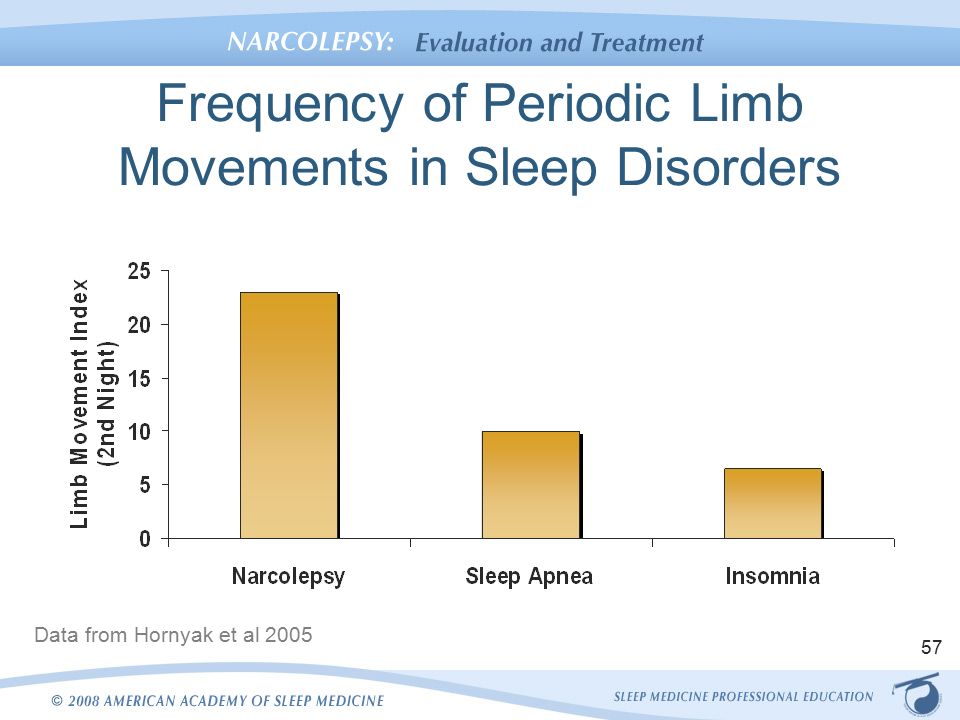

More likely than not, cases or RLS further present additional co-morbidities, particularly sleeping disorders. A whooping 80% of patients diagnosed with Restless Leg Syndrome were also found to suffer from:

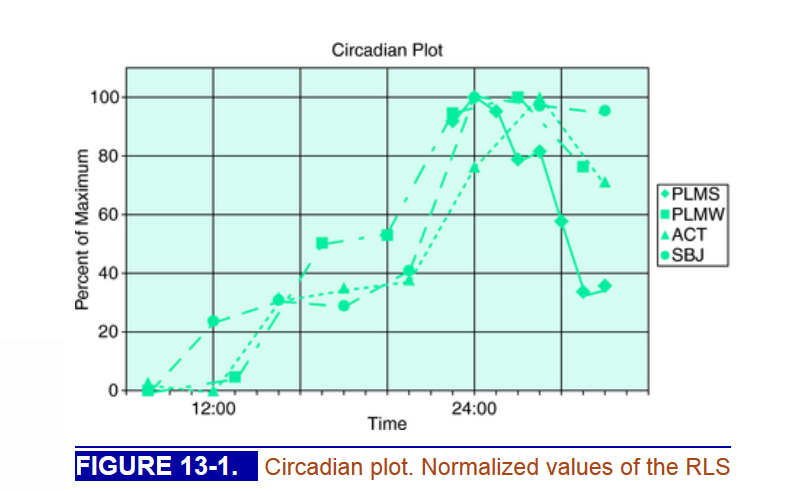

- PLMS – Periodic Limb Movement in Sleep

- PLMW – Periodic Limb Movement in Wakefulness

( PLMS Comorbidity with Sleep Disorders – Image Courtesy of slideplayer.com )

The general consensus on the impact of RLS on the affected person is the negative impact it has on their sleep and normal sleeping pattern, especially since most complain of impaired sleep and struggling to fall asleep (initiation of the sleep phase). Where PLMS is co-morbid, the ability to stay asleep (maintenance of the sleep phase) is naturally complicated further.

( Circadian Rhythm Plot of PLMS and PLMW – Image Courtesy of clinicalgate.com )

Another co-morbidity linked to the RLS-PLMS condition pairing is Sleep-Related Eating Disorders which are, to no surprise, more common among the female population aged between 20 and 30 years old.

( Sleep-Related Eating Disorder – Image Courtesy of www.omicsonline.org )

Symptoms to look out for in this dysfunctional trio are repeated episodes of automatic and abnormal consumption (eating and drinking) in the middle of one’s sleep; the behavioral manifestations are rather strange and may involve ingestion of edible and or unconventional food items (raw, uncooked, cold, frozen, rotten, stale), animal feed (such as pet feed for cats and dogs), inedible substances, and even toxic substances.

( Sleep-Related Eating Disorder – Image Courtesy of www.daftynews.com )